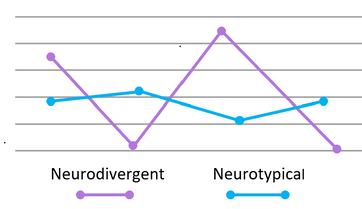

One of the things that can be most perplexing and difficult to wrap your head around when it comes to supporting a neurodivergent person is their tendency to have a spiky profile. We often expect someone with high support needs in one area to have them in other areas as well. If someone needs assistance brushing their teeth, we are not surprised when they need assistance getting their laundry done too. But it might surprise us if we found out that woman at the office who is an absolute wiz at math really struggles with getting her laundry done. We are likely to think she is just lazy or a messy person. Another thing that can be difficult to make sense of are the seemingly contradictory messages out there about being neurodivergent. Is it a disability or a superpower? Is it just a different neurotype? If someone tells you they are autistic or have ADHD, should you be envious or feel sorry for them? It can be a lot to sort through. And that’s where understanding the spiky profile becomes essential. Have you ever heard of an axolotl? They are these tiny salamanders in Mexico, and have been described as a biological wonder due to their ability to regenerate organs—including hearts and spinal cords! But despite what would seem like a superpower that could enable them to live forever, axolotls are endangered. They are extremely sensitive to pollution, and human activities are threatening their survival. This is a classic example of what it means to have a spiky profile. With a spiky profile, you may be unusually good at some things and especially challenged in others. That uncanny ability of the axolotl to regenerate limbs is quite exceptional. And yet the extra sensitive skins they have make them quite vulnerable at the same time. Vulnerable enough that human pollution could very well wipe them out. Spiky profile, indeed. Now we are all good at some things and not so good at others, but when it comes to the neurodivergent, there tends to be much greater differences between the two than there is for neurotypicals (see the graph above for reference). I think back to when I was a young adult. I breezed through college and attended graduate school with a full scholarship and teaching stipend, but by the time I earned my MA at 23 I still did not have my driver’s license. I had failed the test three times and finally went out to a small town that had less overwhelming sensory input and was able to just barely pass. I did my best to conceal my challenges though. There was no way I was going to draw attention to my inability to drive a car! Back then we did not talk about the phenomenon now known as ‘masking,’ but that’s exactly what I was doing. Masking is when you hide or disguise parts of yourself in order to better fit in, and I think it is one of the main reasons we have a hard time understanding why someone who appears highly functional may need support with things that are often considered basic skills. Neurodivergent people with lower support needs (those who are able to hold jobs) are in a constant struggle to ‘appear normal’ and ‘pass’ in a world that was not designed for them. We are still in the early phases of the neurodiversity movement where there are employers that are actually looking for neurodivergent minds for particular jobs, and the reality is that most employers still do not want to make accommodations for their employees. If you start talking to your boss about replacing fluorescent lights and strongly scented chemical cleaning products, you are usually written off as a high maintenance princess who needs to learn to be a better team player. And since the challenges that come along with your neurodivergence usually means you have more expenses than other people (more medical bills, paying three times more for unscented soaps and organic foods to avoid migraines, etc.), you are all the more motivated not to lose your job because the disabling aspects of your neurotype are expensive. This means that a lot of the struggle that high maskers live with has been largely invisible to neurotypicals. General competence in all areas of life is assumed because that’s the story we tell. Or more precisely, it’s because of the parts of the story we leave out. The spikiness goes underground. Unfortunately, the cost of constant masking is often burnout, escalating health issues, and high levels of anxiety. Not cool. These days there is a growing movement to let the cat out of the bag—reveal neurodivergent traits with the hope that society will deem you ‘valuable enough’ to accommodate your ‘vulnerabilities.’ The axolotl is in the same boat. Scientists are very interested in their remarkable regenerative abilities, and so there is hope that this will make them valuable enough to increase efforts at protecting them before it is too late. Understanding and supporting a spiky profile is going to require a shift in the cultural mindset, which I will discuss more in my next post. But in the meantime, let’s start seeing spikiness for what it is—a perfectly natural expression of neurodiversity. There is variation in the natural world, and it is actually the assembly line concept of uniformity that is unnatural. We need to start recognizing, accepting, and even embracing our differences. Let’s give the axolotls a chance to thrive.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |