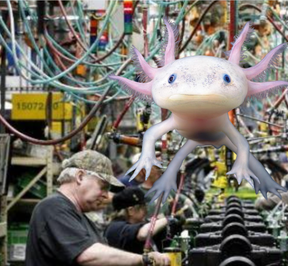

Exploring the Spiky Profile, Part 2 In my last post I discussed what it means to have a spiky profile, where you might be really good in some areas of life but need support in other areas. I pointed out there is nothing ‘abnormal’ about being spiky, and that there are examples of spiky profiles throughout the natural world (axolotls!) that express the diversity of life on earth. If it is perfectly natural though, why do we get so puzzled by the phenomenon? What is it about it that feels so unusual and unlikely? I would like to propose that our difficulty in recognizing and supporting spikiness comes from our deeply entrenched adherence to the factory assembly line model that permeates so much of our culture. That model stems from our value of convenience over everything else. Before there were factories, there was no such thing as uniformity. Our clothes, our furniture, our medicine—everything was handmade, customized, variable. There were no standard sizes, and in fact, people used their body parts to measure things (which is why we still say a ‘foot’ for 12 inches—that was the length of King Henry I’s foot!). Luckily, we are moving farther and farther away from a time when a lot of humans are actually working in factories (although obviously that is still an issue, particularly in certain parts of the world). But the influence of the factory model still seeps into so many spheres of our lives. Fast food restaurants, for example, are designed on the factory assembly line model. It’s all about consistency and uniformity. All the french fries look the same. All the burgers taste the same, every time. Don’t eat fast food and make your own home cooked meals? Ok, but if you’re still buying carrots in the supermarket, they are all going to be the ‘right’ shape and size. A lumpy carrot that is bigger than average will not make it to the grocery store, even though there is absolutely nothing wrong with it. Uniformity is the expectation. Individually, we have not all chosen this value, but it is impossible not to be steeped in it. One area this really impacts us is the modern office environment. Earlier in the 20th century, office layouts were literally based on factory floors, with the later development of cubicles being an upgrade that allowed more privacy. Although they were an improvement, cubicles were still designed as a way of fitting more people into a smaller space. This kind of nudge towards ever greater efficiency is the epitome of the factory model. So how does this relate to being spiky? Well, spikiness is kind of the antithesis of the factory model. It’s all about variation! Just imagine being in a typical office environment where expectations have been shaped by assembly line thinking—an even, consistent output of work is expected for a preordained chunk of time that is consistent from day to day. Now imagine you have ADHD. You may appear to be completely unfocused and unproductive for large periods of time, but can also get into an intense hyper focus and accomplish an astonishing amount in a very short period of time. Are you going to fit in at the office? Of course not! That’s not necessarily a problem if you work remotely (as is becoming more common) and can still meet deadlines, but it’s not the way the conventional workplace was designed to operate. Marching to the rhythm of your own drum is seen as a flaw in an assembly-line culture. And that gets right to the heart of the matter (at least in part). As factory-thinking began seeping into all aspects of life, we started to pathologize anything that did not fit the consistent, packaged, uniform mold we were trained to expect. So some of what ends up being called a disability is actually only a problem because of the way modern life has been set up to operate—we run society like it is one, big, giant factory. But that is only a very recent phenomenon. Factories are relatively new, and their influence in cultural thinking took time to spread. Think back to when humans were hunters and gatherers, by way of contrast. The hypersensitivity that can be hell for the modern day autistic and is currently perceived as a deficit would have actually made them the best at securing food for their tribes. It is the context that makes hypersensitivity problematic, not the trait itself. I do not mean to suggest that this is the entire story though. There can be disabling aspects of being neurodivergent that would be challenging in any context, regardless of the culture. Poor fine motor skills, deficits in executive functioning skills, the tendency to have more trouble with sleeping and digesting food—the list goes on and on. Of course, not all neurodivergents will have all of those challenges and those that do will have them to varying degrees. So some neurodivergent people will feel their traits are largely disabling, while others feel their wiring is mostly a superpower. Often it is a mix of the two. Supporting a person with a spiky profile will require at least two things then: being able to distinguish which areas of challenge are a matter of context and which are true deficits, and choosing to take the time/resources to offer support where it is needed. If you are able to determine that the person is not actually deficient but just needs to do things in their own way, is it possible to give that person the space they need to do so? What is stopping you? And if they do need support, what will having that support enable them to do and become? Can you see the value in it? For some, the thought of providing support can feel like it is going to be time consuming and expensive, but that is not necessarily the case. Think about working remotely—it actually saves money for employers by reducing their overhead, and can help draw and retain workers who wouldn’t apply if they had to come in to the office every day. The biggest investment of energy this all requires is actually in a shift in thinking. We need to reexamine our factory assembly line approach to life and stop judging people based on their ability to conform. Shedding that model will actually allow the spiky folks a chance to excel at what they are really good at. Who knows what kinds of amazing things we have been suppressing by not creating environments where neurodivergent people can thrive! If we can see this shift as a gain rather than a loss, that’s where we will start to gain traction. As long as we are still convinced that there’s nothing better than running the world like a factory, we are not going to get anywhere. So let’s upgrade our model and give those with a spiky profile a chance to thrive.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |